| Silmara Mansur |

By Karine Rodrigues

At the age of 23, Henry Walter Bates, a naturalist with no academic training, set out on an expedition in the Amazon. From a lower middle-class family, he had scant financial resources for the mission, as did his traveling companion, Alfred Russell Wallace, who was also an unknown young man in the British scientific world. On April 26, 1848, in the port of Liverpool, England, they boarded a ship heading for the largest reserve of biodiversity on the planet. They were the only passengers aboard the small merchant ship named Mischief.

For a long time, the history of science was a history of theories that won, of the authors of great theories, of significant equations, of exceptional observations. So Darwin, in this history of evolution, at least in the second half of the nineteenth century, became the principal protagonist. Bates became a supporting actor.

After about six months in Brazil, each followed their own path. Wallace stayed for four years. Bates stayed for 11 years, and judging by the 774-page book he published on his travels in 1863, The Naturalist on the River Amazons, he did not waste a single minute of his long stay in the region. The acclaimed work is still available as a reprint to this day.

In addition to collecting specimens of approximately 14,000 Brazilian species, around 8,000 of which had never been seen in Europe, Bates proposed what became known as Batesian mimicry, observable proof of how natural selection worked.

When investigating butterflies in nature, during one of his excursions to the Amazon rainforest, he identified a physical analogy between different species that was fundamental to the theory of Charles Darwin (1809-1882) and Alfred Wallace. He noted that, in order to deceive predators, the more palatable species imitated colors and patterns from those identified as dangerous, thus increasing their chances of survival. The hypothesis was that these characteristics were passed on to descendants. Mimicry would therefore be one of the forms of adaptation responsible for the transformation of species over time.

Bates' wanderings in the Amazon attracted the attention of researcher Anderson Pereira Antunes. He noticed both the long duration of the scientific expedition undertaken by the Englishman and the fact that the naturalist from Leicester has not received the recognition he deserves in the historiography of the sciences.

In the historiography of science, new perspectives are needed

Why is it that, despite his invaluable contributions, the historiography of science assigned a secondary role to Bates, while the spotlight turned on Darwin and Wallace?

According to Antunes, the fact that the naturalist born in Leicester, England, was a relative outsider contributed to this, given that most individuals in scientific circles in nineteenth-century England came from aristocratic families. Another point against him was that he defended the evolutionary theory of Darwin and Wallace from the start, and it was highly disputed at the time. The British Museum, for example, where Bates dreamed of working, strongly disputed the theories of the author of "The Origin of Species," published in 1859.

Illustrations are in Bates' travel book entitled 'The naturalist on the River Amazons'

There is, however, another reason that helps us understand the place occupied by Bates, says Antunes: “For a long time, the history of science was a history of theories that won, of the authors of great theories, of significant equations, of exceptional observations. So Darwin, in this history of evolution, at least in the second half of the nineteenth century, became the principal protagonist. And Wallace, who published the scientific article together with Darwin, also obtained significant recognition. Bates became a supporting actor."

An aficionado of nineteenth-century travelers' reports since 2012, when he specialized in the dissemination of science, technology and healthcare at the Casa de Oswaldo Cruz and investigated the iconography produced by scientists during scientific expeditions in Brazil in the 19th century, Antunes noticed the presence of other individuals in the illustrations, in addition to the scientists.

Weren't the scenes inconsistent with the stories about traveling naturalists, who are generally portrayed as lonely pathfinders who fearlessly face the setbacks of expeditions to remote regions of the planet?

Antunes found the answer during his master's and doctoral studies in the History of Science and Health, undertaken at the Casa de Oswaldo Cruz. In both investigations, he analyzed sociability in the work of traveling naturalists, under the guidance of Luisa Massarani and co-supervised by Ildeu de Castro Moreira, of the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ).

Essential but invisible collaborators

After his master's thesis, The network of invisibles: an analysis of assistants in the expedition of Louis Agassiz to Brazil (1865-1866), for his doctorate — completed in 2019 after an exchange period in the Department of History at King's College London, in the United Kingdom — Antunes focused on Bates' relationships with different groups during his time in Brazil, especially with local residents. He wanted to find out how they contributed to the success of the naturalist's exploratory journey.

The naturalist was never alone. It is interesting to try to understand these relationships and how knowledge arose from them. Science was produced through these relationships. It did not exist in a void. It was part of a complex set of elements

"Investigating how these interactions took place is a way to better understand the social aspect inherent in naturalist fieldwork and to draw attention to a complex network of individuals generally made invisible in narratives about the great scientific journeys of the nineteenth century, but often mentioned by the naturalists themselves in their travel accounts due to their continuous collaboration,” he writes in his dissertation A naturalist and his collaborators in the Amazon: the expedition of Henry Walter Bates to Brazil (1848-1859).

Through a thorough analysis of primary sources, especially the first edition of the naturalist's report of his travels, as well as field notebooks, personal correspondence and periodicals of the time, Antunes identified 221 individuals mentioned by Bates. In this way, he was able to reconstruct the network of the main individuals with whom the British naturalist was in contact during the expedition to Brazil.

In addition to the recipients of his letters, including Darwin himself, and the agent Samuel Stevens (1817-1899), who sold the specimens sent by the travelers to England, Bates was in contact with prominent individuals in Brazilian society and local and riparian communities, including indigenous people, slaves and freedmen. According to him, the participation of locals is clear in the description of daily exploration activities, such as incursions through the forests and hunting and capturing specimens.

The contributions of indigenous cultures in the writings of Bates

“The naturalist was never alone. Nor did the indigenous peoples, the slaves, and individuals in the riverside communities live there without contact with the foreigners who suddenly appeared in the region. It is interesting to try to understand these relationships and how knowledge arose from them. Science was produced through these relationships. It did not exist in a void. It was part of a complex set of elements," stresses Antunes.

|

|

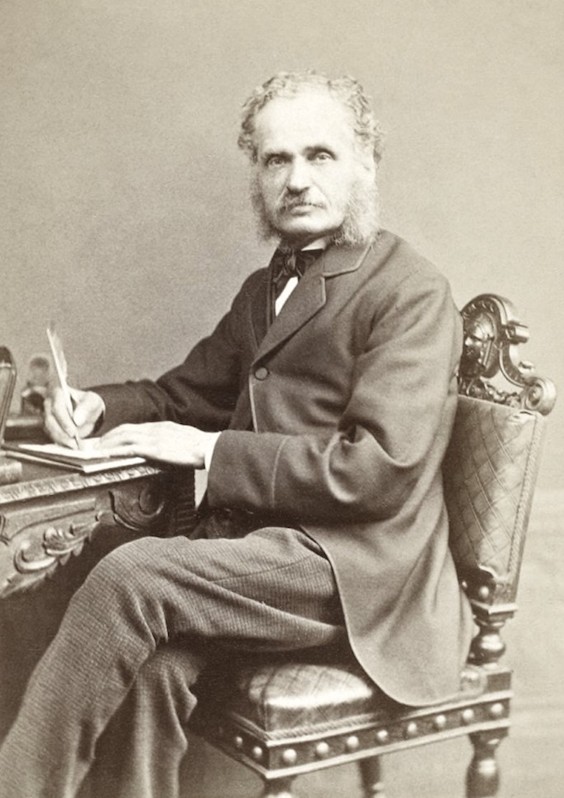

British naturalist Henry Bates. |

In his investigation, the researcher noted that Bates built closer ties with the local inhabitants over time, especially through learning their languages. In addition to Portuguese, he learned the "general language," used at the time among the catechized Indians. Thus, he felt more comfortable interacting directly with locals without the need for external mediators.

The fact that he had limited financial resources for the undertaking in Brazil — contrary to the situation of naturalists like Agassiz, who had already received international recognition as a professor at Harvard University and had the backing of a patron — also aids understanding of the relationships maintained by Bates. He needed to create ties to prepare the structure needed for the expedition.

Analysis of networks uncovers ties

After investigating the texts, which proved the importance of Bates' local collaborators in Brazil, Antunes used social network analysis, a method that allows visualization of the ties established between individuals in a given group. Using Gephi, a free graphical visualization platform, he produced graphs of the details of the British naturalist's network of collaborators. By analyzing the social network, explains Antunes, the center of the investigation moves from the individual biographical level to interactions within the group.

"The focus on the plural, rather than the singular, allows us to evaluate the specific characteristics of the individual interactions that connect the participants of a network and analyze each interaction not only in terms of what it meant for one individual, but rather its significance for an entire community," he highlights in the dissertation, citing the importance of historians mastering digital tools, which also help disseminate the research.

Translated by Naomi Sutcliffe de Moraes